Farmer’s Guide to Trucking Regulations available to Ohio Farm Bureau members

The guide includes a farm driver checklist, overview of state and federal regulations and exemptions, CDL qualifications and more.

Read More

The fabric of their lives holds more than symbolic meaning for Carrie and Robbie Davis. They are weaving an unusual agribusiness that encompasses everything alpaca, from raising the charming Andes natives to chic fashions made from delicate natural yarns on their farm, called Blessed Criations Alpaca Ranch.

Instead of dreaming of their thriving mill, where alpaca farmers from as far as Hawaii and Canada now ship their annual fleece crop for transformation into skeins of yarn, the Preble County Farm Bureau members initially only wanted a few alpacas for breeding purposes. Plus they figured on saving a bit on mowing costs by having the animals graze a few of their six acres, said Carrie, a Preble county Farm Bureau board member.

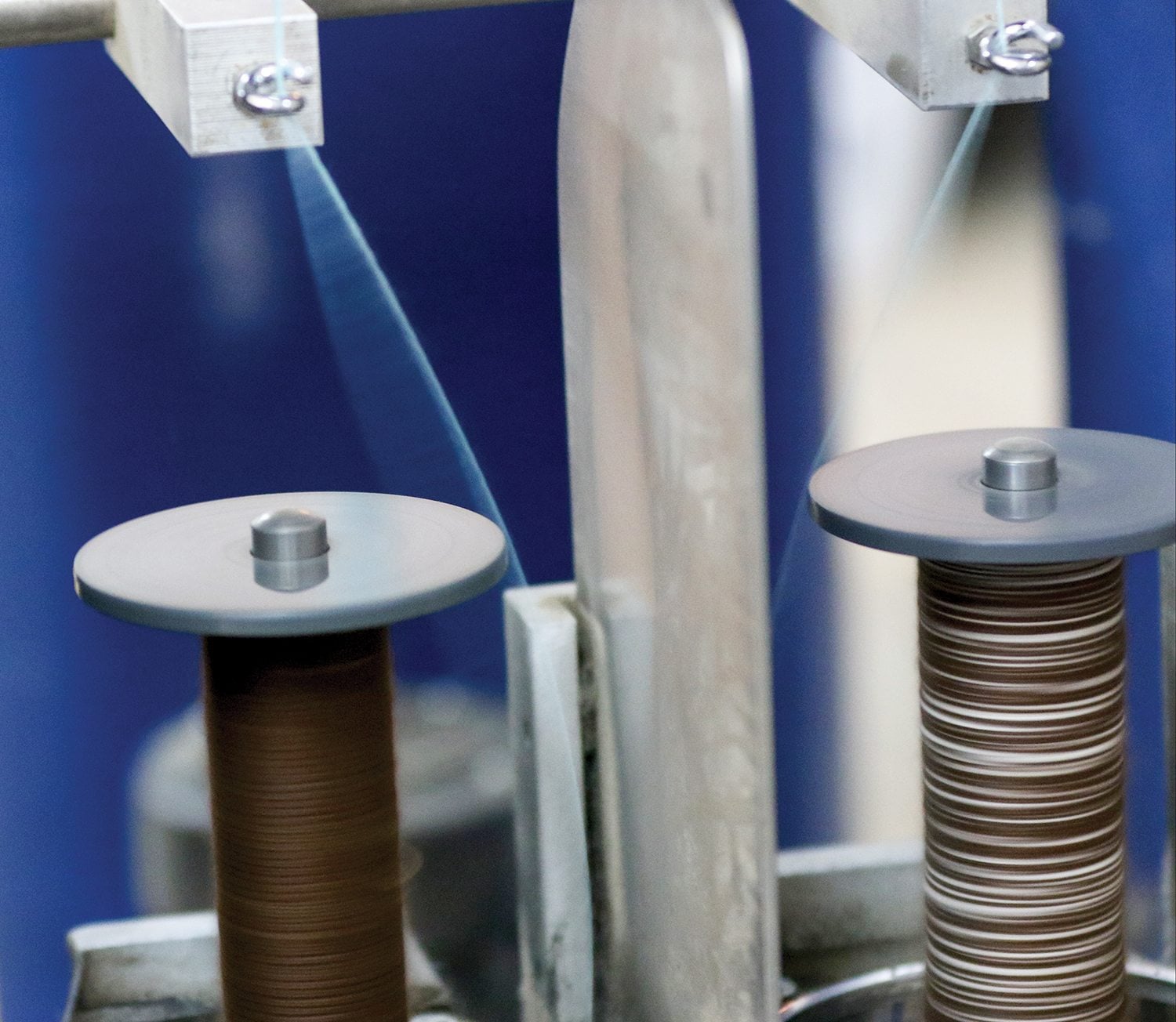

“It was never in my mind to do this,” Robbie said as he glanced at the humming, blue machines of America’s Natural Fiberworks near Somerville. They turn hair into yarn that can become a featherweight scarf retailing for $70 to $80. Blending alpaca, mohair, cashmere, yak, silk or other fibers adds to the value of the fabric.

On the other side of the wall is The Yarn Barn. The retail shop offers skeins of yarns, in both natural colors and dyed, plus rugs, shawls and socks.

A steady commercial customer for about three years is Anne Hanson, fashion designer and founder of the online retail outlet, Knitspot. Based in Canton, the company offers patterns and yarns to knitters looking for natural fibers. She deals mainly with small mills and farmers for “farm to fingers” artisan yarns.

“Working with Carrie and Robbie has been great,” she said. The Davises use no chemical treatments to make the fibers easier to spin or softer, a must for Hanson and her customers.

Another draw – their ability to make special blends in quantities as tiny as three skeins.

Yarn isn’t the only thing that’s been spun in the Davis’ lives – career, houses, work schedules and their original alpaca goals have all changed in the last 11 years.

In a sense their story started in kindergarten, where they were friends. Carrie’s parents knew Robbie’s dad. “Ours is as close to an arranged marriage as you can get,” said Carrie with a smile. They wed after graduating from Mason High School.

Because of growth and development in the Mason area, they sought a more rural location and moved to Preble County. Their interest in alpacas was sparked after Robbie’s father read an article on raising alpacas for profit.

They were hardly alone in looking at this as a means of helping make their few acres generate extra income. After alpacas began arriving in the United States through northern Ohio about 35 years ago, many small Buckeye State breeding farms sprang up. Ohio once was nicknamed Little Peru, Carrie said.

The Davises expanded their alpaca horizons, taking a weekend class in shearing. Because the law requires annual shearing of fleece animals, there’s always a demand for this service. Word spread. Eventually they were doing about 400 head a year. That’s a lot of fleece; an alpaca produces about five pounds annually.

About nine years ago, they realized the sustainable aspect of alpacas was fleece. Thoughts turned to a mill. “The mill was the step to help ourselves and the industry,” Robbie said.

Finding financing among skeptical bankers took about four years. The Davises could qualify for loans to buy yachts but not mill equipment. After clearing that hurdle, they bought a gently used mini-mill from Canada, where it was manufactured. New equipment costs $250,000, Robbie said.

They also moved from what had been their dream home, because township regulations didn’t allow the home-based business they planned.

After setting up the mill, they worked seven days a week for 18 months before making the transition to their present operation. During that long stretch, Robbie continued full-time as an ironworker on construction projects as he followed in the footsteps of an uncle and grandfather. They also sheared.

Their son, Jessie, now 16, “has been with us since the beginning, through all the ups and downs,” Carrie said. He helped with birthing alpacas and their care and has shown them at fairs.

Last year 6,500 pounds of fleece was processed at their shop. So far this year it’s more than 8,000 pounds. They process about 36 pounds a day. It takes 10 to 12 months to transform fleece into fiber.

“When anybody comes to buy alpacas from us, they get this tutorial. They are set up so much better than we were,” Carrie said.

Although it’s not a traditional farm or ranch, they have an end “crop” – clothing – and inputs typical of any livestock operation, from hay to veterinarians to electricity to run the mill.

Their farm consists of a brick-and-frame house and tidy white utility buildings, similar to other farmsteads scattered throughout southwest Ohio. This belies the small, humming mill where UPS, FedEx and the postal service deliver bags of fleece from 40 states and parts of Canada.

“It’s been pretty humbling to reach as far as we have and reach as many people,” Robbie said.

Fiber facts and more

Fibers – Fibers are measured in microns. A single micron is .000039 of an inch. Human hair ranges from 10 to 200 microns.

With fleece, the lower the number, the finer the fiber. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, alpaca ranges from 20 to 70 microns; angora 14 to 16; cashmere, 14 to 19; silk 10 to 13; merino wool, 16; and coarse, hairy wools, 40.

Colors: The 22 natural alpaca colors range from the darkest chocolate to frothy champagne.

Spitting: Alpacas generally only spit at each other.

Crafts: Twice a month open craft nights are held, featuring knitting, crocheting and weaving.

Contact: 513-276-0528, blessedcriations.com or americasnaturalfiberwork.com

ilovetheyarnbarn.com

Photos by Tony Tribble

The guide includes a farm driver checklist, overview of state and federal regulations and exemptions, CDL qualifications and more.

Read More

The plan has been updated to give sole proprietors access to more rate stability and a smart solution that offers potential savings on health care.

Read More

The American Farm Bureau Federation, in partnership with Farm Credit, is seeking entrepreneurs to apply online by June 15 for the 2025 Farm Bureau Ag Innovation Challenge.

Read More

Adele Flynn of Wellington has been elected treasurer of the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation and now holds the third highest elected office in Ohio’s largest and most influential farm organization.

Read More

Producers are urged to work with their veterinarian to practice enhanced biosecurity measures and review and limit cattle movements within production systems.

Read More

The changing seasons bring with them the need to thoroughly inspect pole barns for any damages that may have occurred during the winter months.

Read More

Hundreds of Ohio businesses and sole proprietors are raving about Ohio Farm Bureau’s Health Benefits plan with lower, predictable costs and easy enrollment and administration options.

Read More

AgriPOWER Class XIV spent a few days in March in Medina and Wayne counties learning more about northern Ohio agriculture from leaders in Ohio Farm Bureau.

Read More

Leading Ohio Farm Bureau’s 2024 YAP State Committee are Luke and Kayla Durbin of Coshocton County, Tim and Sarah Terrill of Montgomery County and Carly Fitz of Perry County.

Read More

Farming is a very rewarding occupation, but it can come with hazardous territory if there are not proper training protocols in place.

Read More