Applications for Ohio Farm Bureau Health Plans now available

Members have three ways to apply: contacting a certified agent, calling 833-468-4280 or visiting ohiofarmbureauhealthplans.org.

Read MoreThe Woodmizer sawmill buzzes in Steve Gorby’s pole barn near Lancaster. It’s steadily cutting a 12-inch by 12-inch yellow pine beam salvaged from an 1850s warehouse in Cincinnati into 1-inch by 10-inch boards. Suddenly the blade catches and the machine stalls.

“It could be a nail,” said Gorby to his son Chris who helps out with the family’s Logs to Heirlooms hardwood milling company. The two run a magnet over the beam checking for some form of embedded metal.

“Nails are our No. 1 problem with reclaimed timber,” Gorby said. “But this is probably just a worn-out blade.” The pair set about replacing the saw’s damaged band.

Gorby, a Fairfield County Farm Bureau member, is one of many entrepreneurs in Ohio who is taking the beams from Ohio’s historic barns and other structures and turning them into useful carpentry products. The yellow pine will go to flooring and trim for restoration of the historic Mithoff Hotel in Lancaster. Others are turning ancient oak, ash, hickory, maple, walnut and chestnut beams into everything from furniture to picture frames.

“Most of the year there are probably a dozen crews working across the state dismantling barns,” said Dan Troth, vice president of the organization Friends of Ohio Barns. “They are being hauled to Texas, California, Utah, Colorado, the East Coast – anywhere that doesn’t have big, beautiful timber-frame barns like ours,” said Troth who is president of GreenTech Construction in Delaware.

He understands the dilemma farmers face with their old and often decaying barns. “Our bank barns were built to thresh wheat and hold fodder. They aren’t big enough to store today’s farm equipment. As farmers get bigger they look at costly repairs, insurance, taxes, liability. Pretty soon they see a $75,000 roofing and foundation repair and say, ‘I can build two pole barns for that.’ They call a salvage operator who takes what he wants and buries the remains in a hole.”

To Troth that’s akin to killing an elephant for its tusks. “I want to save the elephant,” he said. “We owe that to the agrarian heritage that made Ohio what it is today. Unfortunately, I’d estimate that fewer than 5 percent of the barns that are taken down end up being rebuilt as barns.”

Pamela Whitney Gray who helped her father Charles Whitney, known as The Barn Doctor, write the book Ohio Barns: Inside and Out, agrees with Troth.

“There’s certainly been an uptick in the interest in repurposing Ohio barns the past few years, but not nearly enough,” she said. “So much of the reuse has focused on taking the oak beams and cutting them up for boards. Most barn restoration has focused on higher-end housing and retail space and restaurants. Sadly, it’s priced out of the reach of the middle class. But barns are big, open inviting spaces. I’ve seen examples of one barn turned into three town houses. There are many examples of barns becoming community centers or venues for weddings and celebrations.”

Franklin County Farm Bureau members Doug and Beth Morgan, who head up the Mt. Vernon Barn Co., are taking steps to find new purposes for historic barns. The firm has repurposed about 25 barns in its five-year history. Morgan, a semi-retired attorney, said his goal is to repurpose 100 Ohio barns.

“That number may not be realistic, but we are finding new ways for people all across the country to put these handcrafted sculptures to use. For me it’s all about the barns finding relevance in today’s life.”

One of the Morgan’s most prominent new-use barn conversions is the Wells Barn erected at Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Columbus. An outreach and educational facility for the park, the Wells Barn is fully booked hosting weddings and meetings year-round. The barn originally belonged to the Garber family in Richland County. The ends were expanded to provide more than 12,000 square feet of meeting space. In just two years the $5.7 million project, which included a new kitchen and landscaping, has more than covered its production costs.

Morgan, who has built homes, party barns, additions and wine-tasting venues from Ohio barns and log houses, is especially pleased when the former owners of the barn are able to meet the new owners and see their barns put to use.

“We try to arrange those meetings so they can share their stories about the barn and extend the historic value of these incredible works of craftsmanship and art.”

Steve Gorby agreed. He recently visited with a barn owner who hoped to move the family barn from its existing location to make a new home.

“That will be a big job for us,” he said. “You hate to see this irreplaceable wood go back to the worms. But to save the structural heritage and preserve the craftsmanship of these master timber framers would be especially rewarding.”

While most of us may want to be younger, many hope their barns are older than they actually are. That’s an observation from Nick Wiesenberg, geological technician at The College of Wooster. Wiesenberg provides the technical support and logistics to date when timber-framed barns or homes were built based on dendrochronology of the structures’ beams. The work is also integrated as part of a class on climate change.

The technique employs a small diameter core sample drilled from numerous beams containing the outermost ring throughout the barn. A series of 10 to 15 of these cores is used to determine the age of the trees and what year they were cut. The core is mounted, finely sanded and examined under a microscope to obtain accurate measurements from each annual ring. Each sample’s ring series is then statistically matched with a computer program and adjusted accordingly to create a floating series that aligns the cores’ unique pattern.

“We know that the build dates of the barns we are looking at fit into a window of time typically between 1800 and 1900,” Wiesenberg said. “We then compare the floating ring-width data with historical chronologies from nearby structures that cover a timespan from about 1600 to 1900.”

The computer calculates where the samples fit best therefore providing an exact span of dates on each sample. Based on the growth of the outermost ring, they can even tell at what point of the year the tree was cut.

“Most of the time we find the trees were cut after leaf fall,” Wiesenberg said. “That would enable the settlers to work on squaring up the trees in the winter when they did not have field work to do and temperatures were more comfortable for felling trees and converting them into beams by hand.”

Examining structures mainly in the area between Cleveland and Columbus, the class has found most of the timber-framed barns and homes were built between 1820 and 1880. Circular saw marks on girts and braces generally indicate a barn was built after the Civil War when steam powered sawmills became more common. Better roads later also enabled easier movement of large milled timbers.

The oldest tree they have examined was a white oak which began growing before 1550. According to Wiesenberg, the earliest structure the college has dated was a house in the Columbus area built circa 1796. They find oak, ash and chestnut beams provide the most reliable ring structure for accurate dating. Unlike carbon dating which is typically accurate to within approximately 50-100 years, dendrochronology can provide a date that is plus or minus zero. Wiesenberg admits, “Every tree has a story to tell but it takes a special ear to know how to listen.”

Photos by Doug and Beth Morgan

Members have three ways to apply: contacting a certified agent, calling 833-468-4280 or visiting ohiofarmbureauhealthplans.org.

Read More

Ohio Farm Bureau recently sent a letter to Congress calling for the swift passage of the Farm, Food, and National Security Act of 2026 (HR 7567).

Read More

House Bill 646 would establish a Data Center Study Commission to examine the impact of rapid data center development across the state.

Read More

Collegiate Farm Bureau serves as a connection to current industry professionals and equips the next generation with the essential tools and resources needed to excel in their careers.

Read More

Ohio Farm Bureau members met one-on-one with state legislators and staff to discuss policy priorities impacting Ohio’s farms and rural communities.

Read More

Legacy nutrient deductions enable new farmland owners to claim deductions on the nutrients within the soil on which healthy crops depend.

Read More

Farmers, agribusinesses and community members are encouraged to nominate their local fire departments for Nationwide’s Nominate Your Fire Department Contest through April 30.

Read More

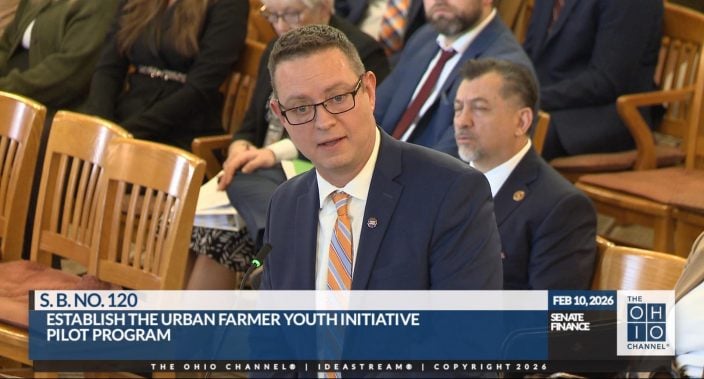

Introduced by Sen. Paula Hicks-Hudson, SB 120 would establish the Urban Farmer Youth Initiative Pilot Program.

Read More

Gases, vapors, and fumes can all create risk. How can we measure and protect ourselves from them?

Read More

The Ohio Farm Bureau’s Young Agricultural Professionals State Committee has named its 2026 leadership and the individuals who will be serving on the state committee for 2026-2028.

Read More