Farmer’s Guide to Trucking Regulations available to Ohio Farm Bureau members

The guide includes a farm driver checklist, overview of state and federal regulations and exemptions, CDL qualifications and more.

Read More

Full stop.

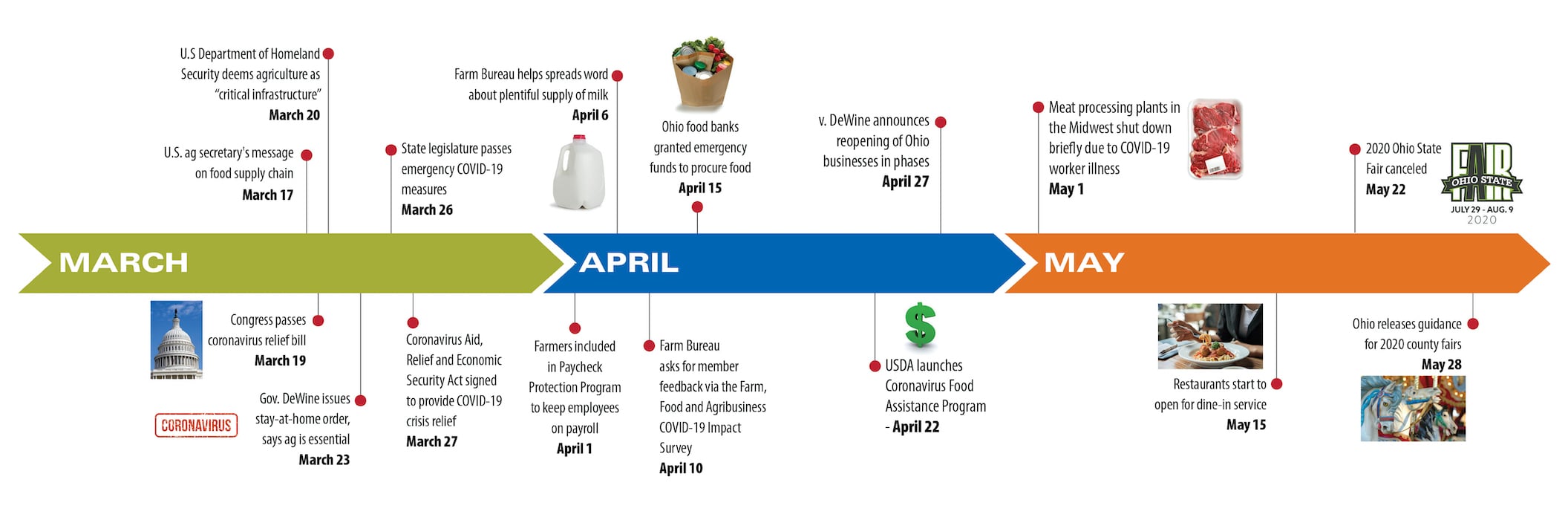

The first case of COVID-19 was officially diagnosed in Ohio March 9, and the Ohio Department of Health ordered everyone to stay at home beginning March 23.

Suddenly, schools across Ohio closed. Downtown office buildings emptied. Grocery stores were overrun, as people stocked freezers and pantries like they were never leaving their homes again.

And for a while, they didn’t, unless they were an “essential worker” — the people who keep the world running in times of crisis — like farmers.

On March 17, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue released a video assuring the American public the food supply chain “remained strong” and that “food and essentials are available.”

However, customers were panic buying. First it was toilet paper, cleaning supplies and hand sanitizer. Then it was flour, bread, milk and meat.

Stories about supply chain disruptions that caused some dairy farmers to dump milk while grocery stores limited sales made headlines in early April. Ohio Farm Bureau worked with American Dairy Association Mideast to quell rumors of a milk shortage and asked grocery stores to lift their limits.

As April rolled into May, and COVID-19 spread into meat processing plants, livestock farmers were impeded by a delay in having their animals harvested. Ohio producers were hit, but meat stayed in stores and farmers kept farming.

In the middle of it all, food banks needed more food and farmers were providing it, but they also were applying for federal Paycheck Protection Program loans to keep their essential businesses running. Farmers across the agriculture spectrum were seeking help from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act to survive the shutdown and adhere to COVID-19 health guidelines when reopening their businesses to customers, among an endless number of other challenges, including a plummet in the restaurant and school lunch segment of the food industry.

The novel coronavirus pandemic lockdown both accelerated and stymied agriculture. The fact that farmers, processors and truckers were essential to sustaining life during the early weeks of COVID-19 was evident, but making sure the supply chain ran smoothly was a challenge.

The food supply chain is more an intricate network of multiple systems than a linear “chain,” as the phrase would suggest. It bent in the early weeks of COVID-19 — but, did it break?

Ohio Farm Bureau asked Jayson Lusk, an economist and department head in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Purdue University; Amy McCormick, Kroger corporate affairs manager, Columbus division and newest member of the Ohio Farm Bureau Foundation board of directors, and Jack Irvin, Ohio Farm Bureau senior director of state and national policy, for their perspectives on the food supply chain during the early days of the COVID-19 crisis.

LUSK: Any system is going to be challenged by a once-in-a-100-year event, but the food sector responded remarkably well to the large and unexpected demand and supply shocks during the pandemic. Overall, across the food system, as long as you were a flexible consumer who was willing to make some substitutions, there were things that were on the shelves that we were able to eat. And within a fairly short period of time, we got back to some sense of normalcy.

Our vulnerabilities have probably been largest where labor use is the highest or where there’s high labor density, so that’s been in some of our food and meat processing facilities and in those more labor-intensive areas of agriculture, particularly fruit and vegetable sectors.

IRVIN: At a time when you couldn’t find toilet paper or hand sanitizer, for the most part you didn’t have any issues getting food. While we had a few hiccups along the way, the amount and access of food was frankly incredible. It shows just how abundant our food supply is and it’s just an amazing testament to our farms and our farmers.

MCCORMICK: Kroger began investing in digital several years ago to build a seamless ecosystem that would deliver anything, anytime, anywhere. As a result, we have over 2,000 pickup locations and 2,400 delivery locations. These investments were especially timely as customer adoption of pickup and delivery grew significantly during the pandemic. And because of our existing ecosystem, we were able to quickly offer in-demand no-contact delivery and low-contact pickup services. We also began testing Kroger’s first grocery pickup-only location in Cincinnati.

LUSK: We were already on a path of more e-commerce in food, and it was accelerated by this pandemic. It’s not impossible for me to imagine a world where the footprint of a grocery store is much smaller than what we have today. Maybe one where we buy most of our bulk items and prepackaged goods online and the actual physical store focuses on fresh fruits and vegetables, or meats, that a lot of us still want to pick out in person. I don’t know that that will happen, but this pandemic has certainly moved us in that direction.

LUSK: Would we be less prone to these shocks if we had a larger number of medium-sized plants? I think it’s a legitimate question that’s worth some investigation, but I don’t think the answers are as obvious as a lot of people think they are. The problem in our meat sector is that we don’t have extra capacity. The issue wasn’t large or small plants. The issue was that when a plant shut down, there wasn’t enough excess capacity at other places to pick up the pieces.

A system with more capacity would be less prone to those kinds of shutdowns, but it’s also very costly. You’re basically asking somebody to build a plant that’s not running at full capacity, and that’s expensive. There’s a trade-off between efficiency and this kind of resiliency. If it’s excess capacity that we’re talking about, there’s a cost that has to be born.

IRVIN: We’ve definitely seen a lot more interest in a regional and local food supply chain and protecting that and having access to food here closer to home. On the livestock production side, when a lot of our major processors either dramatically scaled back their slaughter capacity or had to go completely offline, we saw some pretty tight bottlenecks there, particularly on the beef and pork side. I think we’re going to have to take a longer term look at that. Would we be better served having more diversity of size or some regionalization? What are some of the regulations that might be hindering some of those businesses from opening in some states like Ohio? What are some of the labor challenges? Certainly it’s a complex answer and I think there will be a lot of those conversations moving forward.

MCCORMICK: The importance of a healthy supply chain has never been more critical to our communities than in the face of this global pandemic. As the nation’s largest supermarket retailer, Kroger’s extensive supply chain is constantly evolving to meet the needs of our customers and communities. We reinforced our supply chain best practices by monitoring rapidly changing shopping trends, focusing on in-demand products, maintaining high productivity and prioritizing the health and safety of our associates. Kroger also recognizes we are in a position to help others, so we have created and shared openly our “Blueprint” to help other retailers, manufacturers and businesses maintain operations in a safe and effective manner.

LUSK: There has been interest in more direct-to-consumer, farm-to-consumer type marketing, and I think this pandemic triggered increasing interest in that type of food system. I think the question is “How big do we ever expect that to really be?” It’s a very, very small share of the total food purchases we have today, and it can grow 100% and still be a small share. It’s a different structure, but it’s not one to suit most consumers’ needs.

And both on the farm and in the processing plant, automation might be something we look at more to help alleviate some of the vulnerabilities from labor.

IRVIN: Maybe some of the folks who live in cities take it for granted, but the lack of broadband and internet access was highlighted very clearly — whether you’re talking about the need for it for business, telemedicine or the education side of things. It’s a message that Farm Bureau has carried for a long time, and we’ve worked on the issue for a long time. It’s a difficult situation and it’s a tough challenge to meet, but the silver lining in this pandemic is that it helped highlight the importance of this issue.

LUSK: The pandemic will cause people to think about diversification both in their supply chain and their customer base. This pandemic also revealed how complicated our food systems are and how little most people know and understand them. It’s not as simple as it seems on the surface. There’s a lot of hard work and complicated systems that go into making sure that food arrives on our dinner plate every night. It should tell us how much we take for granted all the time.

IRVIN: The pandemic found holes in the supply chain — that process of getting the food from the farm to the shelves in the home or the restaurant, or wherever that end user is going to be. We need to make sure we have a little more robust system long term. And because the system is complex, there is no one way to do that. We were going a million miles an hour and in a million different directions, trying to put out fires and help all the food system players.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kroger Co. expanded its dairy rescue support program to help process fluid milk for donations to Feeding America food banks and other community organizations, according to Amy McCormick, corporate affairs manager for the Kroger Columbus Division.

As foodservice, hospitality and restaurants closed earlier this year, many dairy farmers did not have a market for their milk. Because Kroger operates 17 dairies around the country, it was uniquely positioned to offer its processing capabilities. McCormick said Kroger manufacturing and dairy procurement teams rapidly scaled a program to rescue surplus milk — donated by Kroger’s dairy cooperative suppliers like Dairy Farmers of America’s (DFA) Mideast Area. Kroger donated the processing and packaging at Kroger-operated dairies, like Tamarack Farms Dairy in Newark, Ohio — and directed it to food banks and families in need. Additionally, in some areas, Kroger’s logistics team will also donate the transportation of the milk to local food banks.

In partnership with its dairy cooperative suppliers and farmers across the Midwest and South, Kroger processed and donated about 200,000 gallons of additional milk to Feeding America food banks and community organizations through the end of August.

The guide includes a farm driver checklist, overview of state and federal regulations and exemptions, CDL qualifications and more.

Read More

Ohio Farm Bureau provides opportunities, platforms and resources to help you develop your voice in the industry and give farmers a seat at the table with leaders and legislators.

Read More

The emergency fuel waiver to allow the sale of summer gasoline blends containing 15% ethanol will lengthen the period during which Americans can continue buying E15 from June 1 to Sept. 15.

Read More

The Small-Scale Food Business Guide covers federal and state regulations for selling food products such as raw meat, dairy, eggs, baked goods, cottage foods, fruits and vegetables, honey and more.

Read More

New resources and technology are broadening the different types of sales tools and strategies available to farmers.

Read More

ODA will enroll 500,000 acres into the program for a two-week sign-up period, beginning April 22, 2024, through May 6, 2024. Contact local SWCD offices to apply.

Read More

Katie Share of Columbus has been named ExploreAg and Youth Development Specialist for Ohio Farm Bureau.

Read More

Mary Klopfenstein of Delphos has been named Young Ag Professional and Ag Literacy Program Specialist for Ohio Farm Bureau.

Read More

The plan has been updated to give sole proprietors access to more rate stability and a smart solution that offers potential savings on health care.

Read More

The American Farm Bureau Federation, in partnership with Farm Credit, is seeking entrepreneurs to apply online by June 15 for the 2025 Farm Bureau Ag Innovation Challenge.

Read More