Applications for Ohio Farm Bureau Health Plans now available

Members have three ways to apply: contacting a certified agent, calling 833-468-4280 or visiting ohiofarmbureauhealthplans.org.

Read MoreWhen the East Coast press wants to do a front page story in a flyover state like Ohio, that usually means it’s election season.

But when The New York Times visited a farm in Blanchester this past March, the story the paper wrote had less to do with politics and policy than with people trying to live their lives in the face of a devastating drug crisis.

Ohio’s drug epidemic became an Ohio Farm Bureau priority issue in 2017, and the Times took note: “Farm Bureau’s attention to seed, fertilizer and subsidies has been diverted to discussions of overdoses,” Times reporter Jack Healy wrote in a front-page story. Healy’s story featured Roger D. Winemiller, a Blanchester farmer who lost two children to drug addiction and is worried about his third child’s addiction recovery.

The drug epidemic has swept into Ohio and taken hold unlike any other health care crisis before it. Opioids. Heroin. Fentanyl. Carfentanil. Meth.

It used to be conventional wisdom that drug problems were confined to the big cities and urban areas. No more.

Drug plight in a small town

Jackson Township Police Chief Jon Schade’s biggest concern in his small jurisdiction of Farmersville in Montgomery County generally revolves around slow farm equipment and the auto accidents that can result from impatient drivers.

Earlier this year, however, the Montgomery County Farm Bureau member acquiesced to public pressure and a plea from the Valley View Community Drug-Free Coalition and made the determination that his officers should begin carrying Narcan.

The nasal spray is an emergency treatment administered to a person suspected of overdosing on opioids. It reverses the effect of the drug and can prevent an overdose death almost immediately.

It’s also controversial.

In Farmersville, Schade said there is a “50/50 split” in opinions of the local populace about whether drug addiction is a disease or the result of bad choices, but for him it came down to a safety issue for his department. His officers have been trained and now carry Narcan in their patrol cars

“We’re in a metropolitan community, but we’re rural,” Schade said. “We have more acres of corn than we have people. We weren’t real hip on (carrying Narcan) but if a drug goes airborne (an officer) can overdose through accidental contact.”

That very scenario played out in May when an officer in East Liverpool accidently overdosed when he brushed off just a small amount of fentanyl powder that was left on his shirt after a traffic stop. The officer needed several doses of Narcan at a local hospital to reverse the effects of the accidental overdose.

While officer safety is a top priority, protecting the community from an epidemic residents sometimes want to pretend doesn’t exist is another.

“Parents in these rural communities don’t want to believe it,” he said. They don’t want to think their own child could become an opioid addict, but there are signs to look for.

“They steal from family first,” Schade said, noting that unused pain medication from a grandparent’s medicine cabinet is often an easy first stop. Then they break into cars and houses, looking for money or items they can sell fast to get money for their next hit.

“Usually they hit rock bottom when they go to jail,” he said, or worse. “We’ve lost more kids to drug overdoses than car crashes over the last few years.”

Living a parent’s worst nightmare

It’s a straight shot down Farmersville Germantown Pike to Beth and Mitch Genslinger’s home in downtown Germantown.

Walking into their house you’ll find small, colorful plastic crates filled with toddler toys and the energetic, hurried footsteps of their 2-year-old granddaughter, Ava. Draped over the back of the sofa in the front room is a throw with a photo of Ava when she was still a baby in the arms of her smiling uncle, Andy.

Andy was a big shot at Valley View High School – a popular kid on the football team. After graduation in 2009, he started to drift.

“He had a lot of depression,” Beth Genslinger said, “but we just thought ‘He’ll find his way through it.’”

It started with a classic gateway drug – marijuana, she said. It wasn’t long before her son was looking for a bigger high.

“A friend’s mother called us (suspecting he was using drugs),” she said. “He was going to school and working; we had no idea.”

When his parents confronted him he didn’t deny it, but he said he had it under control and they believed him.

Shortly thereafter he was diagnosed with Hepatitis C, a liver disease contracted by sharing needles through intravenous drug use. After that he swore off drugs.

“He told us ‘Nope, never again’ and we thought ‘Of course, never again,’” Genslinger said. Soon after he started working at a job he enjoyed, but Andy never wanted to go to rehab and it wasn’t long before he was using again.

At this point his parents were desperate to get him the help he needed. They’d seen their nephew die of a fentanyl overdose 12 years prior and they were scared to death. Rock bottom came when Andy developed a paraspinal infection, also due to intravenous drug abuse.

“It paralyzed parts of his body,” she said. “He was in the hospital for 33 days.”

The irony? He was released with a list of opioid prescriptions to take, she said.

“We hid his medications, gave them to him as prescribed,” she remembers. “He needed 24-hour care to work through this.”

But the addiction ultimately was too strong. His mother found him in his bedroom in October 2015 after he’d overdosed.

Now, Genslinger’s one of the most outspoken advocates of the Valley View Community Drug-Free Coalition. It was a decision she made on the day her son died.

“That’s the road I have to go down for my own healing,” she said. “There is a stigma (attached to drug addiction) and I felt the same way – ‘What will people think of me? I can’t even raise my own child.’ I will not remain silent now.”

The coalition is prevalent throughout the Farmersville and Germantown communities, which make up the Valley View Local School District. One of its public events is called The Jericho Walk. It starts at various churches and comes together at a local park to remember those who are fighting addiction and who died from the drug epidemic. The group speaks at churches and local schools.

It’s something, but sometimes it isn’t enough. Two months after Andy died, his cousin Daniel Weidle also overdosed and passed away. “Out of seven grandchildren, my parents have lost three to drug addiction,” Genslinger said.

How the epidemic grew

While marijuana and alcohol are known as the gateways for eventual heroin addicts, the abuse of prescription opioid pain medication is known as the gateway to the current drug crisis in Ohio.

“This started by people becoming addicted to pain meds,” said Jean Young, director of Family Health Services in Darke County. “It started when people would gauge their pain levels based on a chart in the doctor’s office.”

Prescriptions for legal, albeit very addictive pain medication – OxyContin, Vicodin, Percocet – were being routinely written for patients in significant quantities in an attempt to mitigate their immediate pain. But by the time they were no longer needed for pain, the person was hooked on the drug itself, starting a cycle that has fueled the epidemic seen today, Young said. Once the epidemic began to emerge, when doctors started reigning in prescriptions and state law enforcement started cracking down on “pill mills,” heroin bought on the street became a cheaper way to get high.

Heroin has been around for decades, but its use has skyrocketed as prescriptions have become more unattainable or unaffordable.

“You can get heroin for $5 a capsule,” Young said. “You can get five (capsules) for a bottle of Tide.” To make matters worse, heroin is often now laced with fentanyl and carfentanil, which is 10,000 times more potent than morphine. One dose can kill.

A few years ago the local chamber of commerce approached Family Health Services for help in addressing the addiction needs in the community. Two of the largest manufacturers in the area were struggling to find workers.

“Manufacturers in Darke County and the surrounding areas are having a hard time finding employees who can pass the drug screening,” Young said. “These are decent-paying jobs and they can’t staff their businesses.”

Recruiting drug-free employees is one of the farm community’s concerns with the epidemic, as is rural crime.

Focusing on prevention

Almost 20 people gathered at the Alcohol, Drug And Mental Health board offices in New Philadelphia recently, invited by Farm Bureau Organization Director Michele Specht. It was the latest in a string of public policy development meetings hosted in her four-county region of Carroll, Harrison, Jefferson and Tuscarawas to bring community stakeholders together to discuss the drug epidemic. Farm Bureau meetings like this are being held statewide.

Coming together in May were county Farm Bureau leaders and Ohio Farm Bureau state staff, Prevention Action Alliance (formerly Drug Free Action Alliance), the Tuscarawas and Carroll county anti-drug coalition, representatives from FFA and 4-H, Ohio State University Extension, Nationwide, Ohio state Rep. Al Landis and the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

The goal of the meeting was to begin development of a plan to effectively battle the drug crisis in Tuscarawas and Carroll counties. The first step is data collection, such as a survey taken at an FFA leadership camp, to evaluate county drug abuse trends. The vision is to not only develop a comprehensive plan to help the community but potentially create a framework for other parts of the state to follow.

“Rural America is taking notice,” Specht said. “What can we do to help solve this problem? We really need to bring it back to grassroots and figure out what we can do.”

Harim C. Ellis, director of youth-led programs for Prevention Action Alliance, led the discussion about best practices that successful communities use to establish drug prevention programs in their areas. The methodical approach was embraced, even as the mood of the lively discussion suggested that time was of the essence.

Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine has made combating the opioid crisis a top priority in his office as has Gov. John Kasich. An additional $170 million in funding was included in the state budget to combat the growing drug crisis despite a projected overall budget shortfall.

The urgency that resonates throughout the state was felt during the Farm Bureau-organized discussion in New Philadelphia – so much so that Molly Stone, chief, bureau of prevention for the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, was encouraged.

“I have been with the department for over 20 years and I have never seen a room with this variety of community leaders coming together wanting to take action,” she said. “I think it’s great.”

Note: Farm Bureau is asking members how the drug epidemic has affected families, friends and local communities. Share your thoughts on Ohio’s drug epidemic.

Listen to a Town Hall Ohio radio program on Ohio’s drug epidemic. Guests are Andrea Boxill from the Governor’s Cabinet Opiate Action Team; Tim Maglione from Ohio State Medical Association and Washington County Sheriff Larry R. Mincks, Sr.

Feature image: Beth Genslinger speaks about the struggles her son Andy, pictured in the throw on the sofa behind her, endured as an opioid addict and the Valley View Community Drug-Free Coalition she has been passionately involved with since his death.

Photos by Tony Tribble and Kelli Milligan Stammen

Members have three ways to apply: contacting a certified agent, calling 833-468-4280 or visiting ohiofarmbureauhealthplans.org.

Read More

Collegiate Farm Bureau serves as a connection to current industry professionals and equips the next generation with the essential tools and resources needed to excel in their careers.

Read More

Ohio Farm Bureau members met one-on-one with state legislators and staff to discuss policy priorities impacting Ohio’s farms and rural communities.

Read More

Legacy nutrient deductions enable new farmland owners to claim deductions on the nutrients within the soil on which healthy crops depend.

Read More

Farmers, agribusinesses and community members are encouraged to nominate their local fire departments for Nationwide’s Nominate Your Fire Department Contest through April 30.

Read More

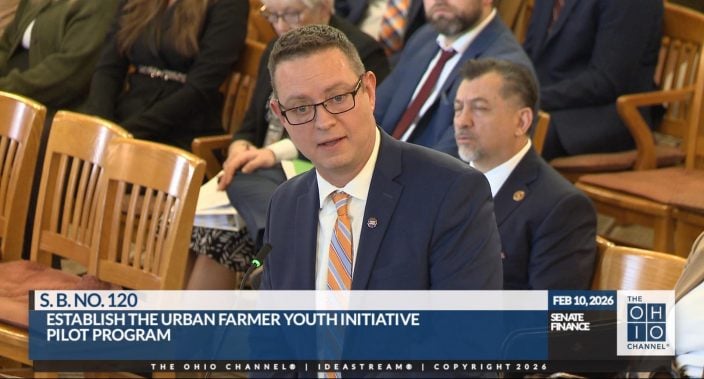

Introduced by Sen. Paula Hicks-Hudson, SB 120 would establish the Urban Farmer Youth Initiative Pilot Program.

Read More

Gases, vapors, and fumes can all create risk. How can we measure and protect ourselves from them?

Read More

The Ohio Farm Bureau’s Young Agricultural Professionals State Committee has named its 2026 leadership and the individuals who will be serving on the state committee for 2026-2028.

Read More

The Ohio Farm Bureau Foundation has multiple scholarships available to Ohio students from rural, suburban and urban communities who are pursuing degrees with a connection to the agricultural industry.

Read More

With 100% bonus depreciation now permanent, farmers can deduct the full cost of a new agricultural building in the year it’s placed in service.

Read More